LABOR & MIGRATION

An Illustration of "Us vs. Them" MentalityPerhaps one of the most damaging outcome of neocolonialism was on the island's society, where social relations were hurt as a result of the hate and discrimination inspired by the French and Spanish use of the “other” and “us vs. them” rhetoric. At one point Haiti invaded the Dominican Republic and occupied it for 22 years (until the D.R. gained its independence in 1844). In the decades since, Dominican elites professed their anti-Haitian prejudices (known as antihaitianismo) and used this as a tool for uniting against the perceived common enemy of Haiti.

An Illustration of "Us vs. Them" MentalityPerhaps one of the most damaging outcome of neocolonialism was on the island's society, where social relations were hurt as a result of the hate and discrimination inspired by the French and Spanish use of the “other” and “us vs. them” rhetoric. At one point Haiti invaded the Dominican Republic and occupied it for 22 years (until the D.R. gained its independence in 1844). In the decades since, Dominican elites professed their anti-Haitian prejudices (known as antihaitianismo) and used this as a tool for uniting against the perceived common enemy of Haiti.

Rhetoric and propaganda pushed ideas that Dominicans were devout Catholics, while Haitians were voodoo sorcerers who believed in spirits and used black magic in mysterious ceremonies. Dominicans began to consider themselves more white than black as the proud descendants of Spanish colonizers, while Haitians were continuously portrayed as the black descendants of African slaves. To be Dominican meant that one was Hispanic (Spanish-speaking) and NOT black, regardless of skin tone. Fears of another invasion from Haiti resulted in the use of rhetoric that propagated discriminatory views and led to increasing calls for actions that limited the number of Haitian migrants and restricted their descendants’ access to Dominican nationality.

Antihaitianismo tensions bled into the 1937 Pasley Massacres, when Dominican dictator Rafael Trujillo (who supported antihaitianismo and Dominican nationalism) not only hired people to distort Haitian-Dominican history and portray Haitians as hostile foreigners culturally and racially inferior to the Dominican people (a romantic notion of Dominican history still shared by many Dominicans today), but also ordered the 1937 massacres of Haitians in the border areas, where many labored in the cultivation of sugar.

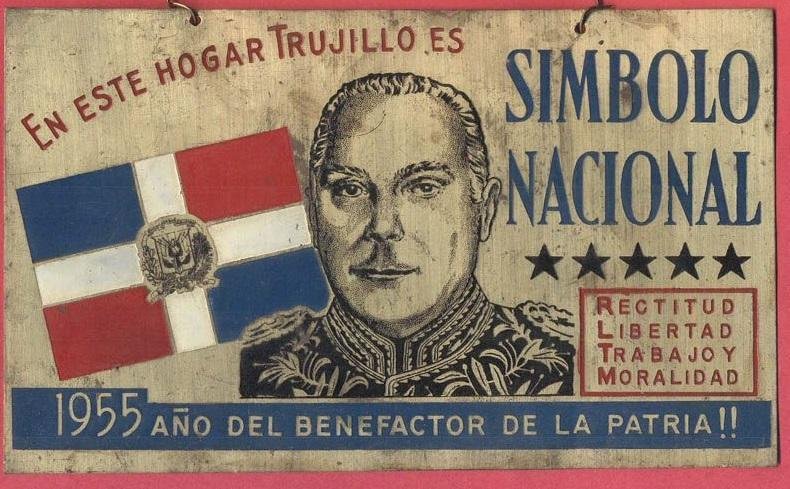

Propaganda from the D.R. stating, "In this home, Trujillo is a national symbol. 1955 is the year of the patriot!

Propaganda from the D.R. stating, "In this home, Trujillo is a national symbol. 1955 is the year of the patriot!

Rectitude, Liberty, Employment, Morality."

For 50,000 Haitians and Dominicans, the pronunciation of the letter “r” was the difference between life and death. The correct answer (one on the side of life) was “perejil” with a trilled (Dominican) “r” sound. For Creole-speaking Haitians, the “r” sound was difficult to pronounce – those who answered with a wide, flat (Haitian) “r” sound were not left alive.

This is like killing people who say puh-JAH-muh-z and only sparing those who will say puh-JAM-uhz! The irony? Trujillo’s own grandmother was Haitian (dictators aren't known for remembering their roots). A pattern emerged in Haiti, one where new leaders would emerge, steal and drain Haitian economy, only to be replaced by another authoritarian leader.

This discrimination had nothing to do with skin tone, yet plenty to do with the class-based systems colonial rulers used to measure and determine people's social status.

Most recently, antihaitianismo has escalated and developed into a migratory problem. When the D.R. finally broke free from its colonial ties with Spain (who did not impose an independence debt on them), Dominicans were able to build infrastructure, create industries, and fund public works that made their people better off. The prosperity a country over incentivized many Haitians to migrate into the D.R. in desperate efforts to escape the poverty of their country.

A Haitian worker crosses the border fence separating the Dominican Republic town of Jimani from the Haitian town of Malpasse, August 26, 2015 (AP photo by Dieu Nalio Chery).

This migration was aggravated by the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, an earthquake from which the country has not yet recovered and thus, prompted even more to migrate to the D.R. in search of employment and a new life. As a result, the D.R. (similar to the U.S.) has professed their problem with “dirty” Haitians coming to their country to benefit from their resources, take their jobs, etc. This growing resentment towards Haitian migrants, combined with a history of antihaitianismo, led to even greater institutionalized racism against Haitians and decedents of Haitian immigrants in recent years.

Amnesty International notes how before 2010, the D.R. had a birthright citizenship policy similar to the one the United States currently has stating that anyone born in the country’s borders is Dominican (except the children of Haitian diplomats). But in 2010, the Dominican constitution was amended to reflect the decision that anyone "in transit” (i.e. anyone born to an undocumented person) could no longer claim Dominican citizenry, regardless if they were born on Dominican soil. In 2013, the Dominican leadership added that the new law would be applied retroactively, all the way back to 1929, to anyone of Haitian descent (Amnesty International, 2015). This means that if anyone in your family entered the D.R. as an undocumented immigrant on or after 1929, then all people who came after them in that family group who were (up until 2010) considered valid Dominican citizens were now revoked of that citizenship.

These new immigration and citizenship laws obviously targeted Dominicans of Haitian descent (an example of legalized institutional racism). The D.R. gave people affected by this law until August of 2015 leave the country, and thereafter established that those still in the country after that deadline of voluntary departure were subject to deportation. Under these new stipulations, the people now getting deported were born in the D.R. back when it was promised to them that they would be citizens because they were born on Dominican soil. Thus, most of the deportees have never been to Haiti or known any relatives there, since many families migrated to the D.R. generations ago.

Therefore, this amendment not only deported them to a country they have no ties to, but also resulted in them being “stateless” since they do not legally belong as citizens of either the D.R. or Haiti (Haiti does not accept them as citizens either).