View even more videos and documentaries describing the immigration and labor problems presented on this site. Happy learning!

Read MoreHow does a country with such destitute conditions exist on the doorstep of the United States of America?

“It is astonishing how much money can be made out of the poorest of the poor with a little ingenuity.”

- Graham Greene, The Comedians

It is this disturbing question that begs an answer from those of us living in the very hands of prosperity and justice to invest in a better future for the Haitian people.

Haiti, a country rich in culture and community, remains the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere. It is among the poorest countries in the world. It is crippled by political, economic, environmental and social instability. Of their estimated population of 11 million, masses of Haitian people fight to simply survive each and every day. While in a continued state of political unrest, which intermittently (and currently) freezes life and business in the country’s port areas, over 80% of the Haitian people live in poverty. Many families are without access to clean water, health care, proper lodging, or an adequate food supply. Haiti is extremely vulnerable to natural disasters, with more than 90% of the population at risk, and this is no coincidence.

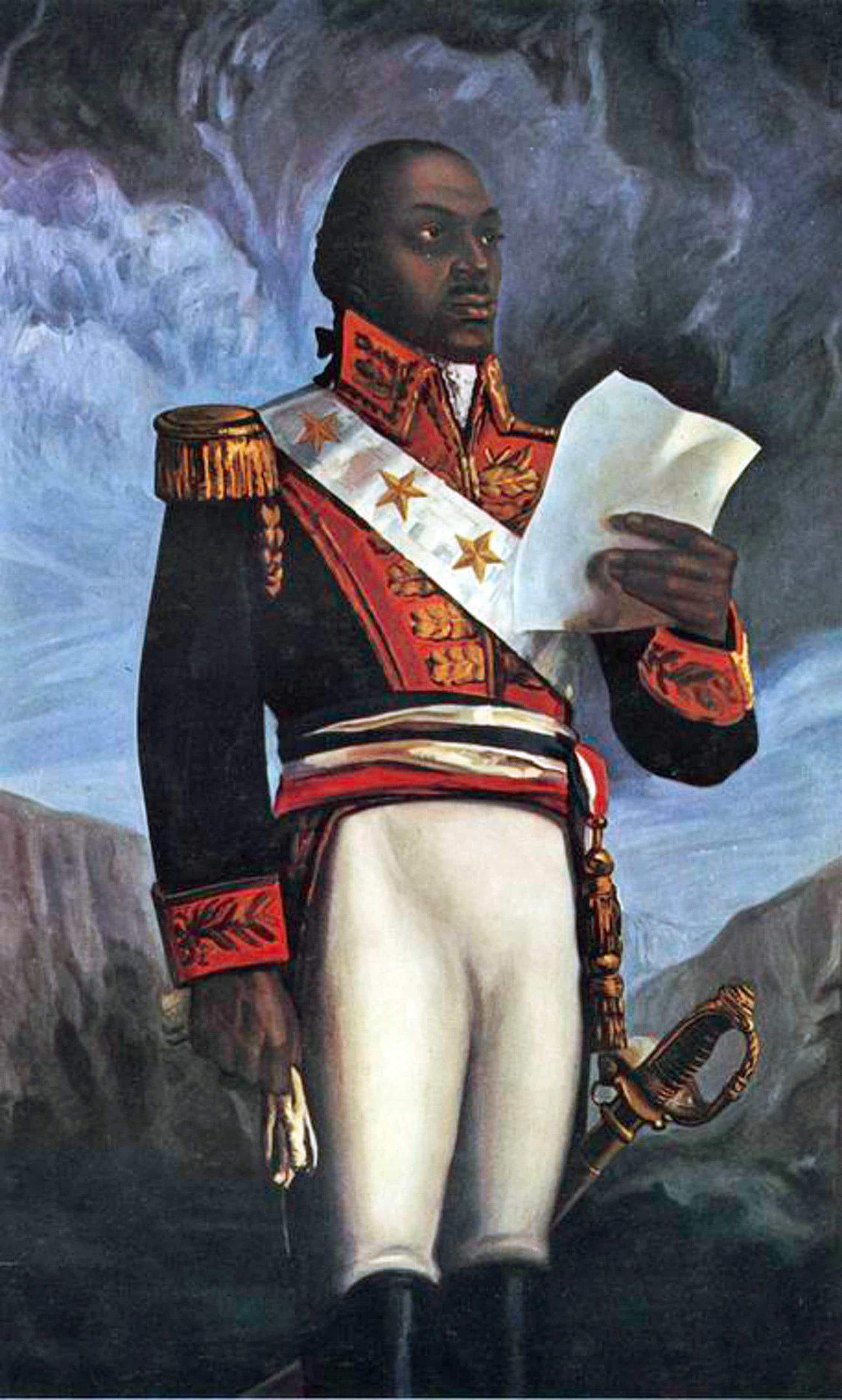

Greene’s statement on the country of Haiti is still relevant today, for history has seen how this nation has been repeatedly exploited by the French, Spanish, and American empires long after it declared independence in 1804. This exploitation, first through colonialism and then through neocolonistic endeavours, has resulted in the stunted growth of a nation that despite its almost 530 years of recorded history remains at the bottom of the global food chain.

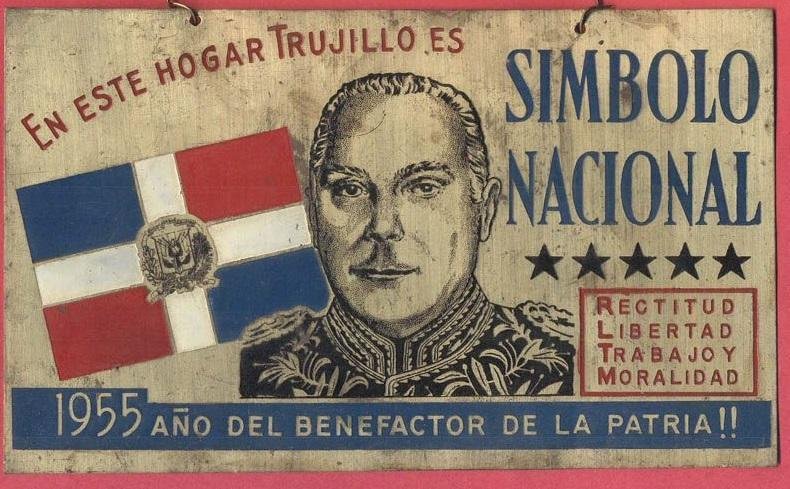

Using dependency and world systems theory, we analyze how Haitians (like so many other colonized people) continue to suffer economically, environmentally, and socially from the damaging long-term effects of their colonial history. While we focus specifically on educating the public about current problems like international migration and labor, it is important to note how visible these effects are expressed today in the form of relations that extend beyond European powers, like that of Haiti’s with the Dominican Republic.

What makes Haiti unique is that this seemingly insignificant country about 5X smaller than Florida has inspired almost three centuries’ worth of revolutions as the first true birthplace of universal rights for African slaves. This contribution to world history and progress is often downplayed by Western knowledge-makers and even Haiti’s own officials, who have taken this credit from Haiti and instead used their portrayal of her supposed incompetence as a nation to justify how they can continue to capitalize on her resources and ignore that she and her people deserve more than the treatment they have received in the past.